Blood donation is vital to healthcare systems worldwide, supplying essential life-saving resources to patients in need. With every donation, an intricate process unfolds, designed to ensure the safety and efficacy of the blood supply. While routine tests cover various infectious diseases and blood type, leukemia screening is typically not among the criteria assessed. This oversight highlights a gap in commonly understood protocols, emphasizing the complexities involved in blood screening. However, the procedure serves a greater purpose beyond merely collecting blood; it plays a crucial role in public health surveillance that can isolate potential medical conditions.

Mini Health Assessments: A Gateway to Awareness

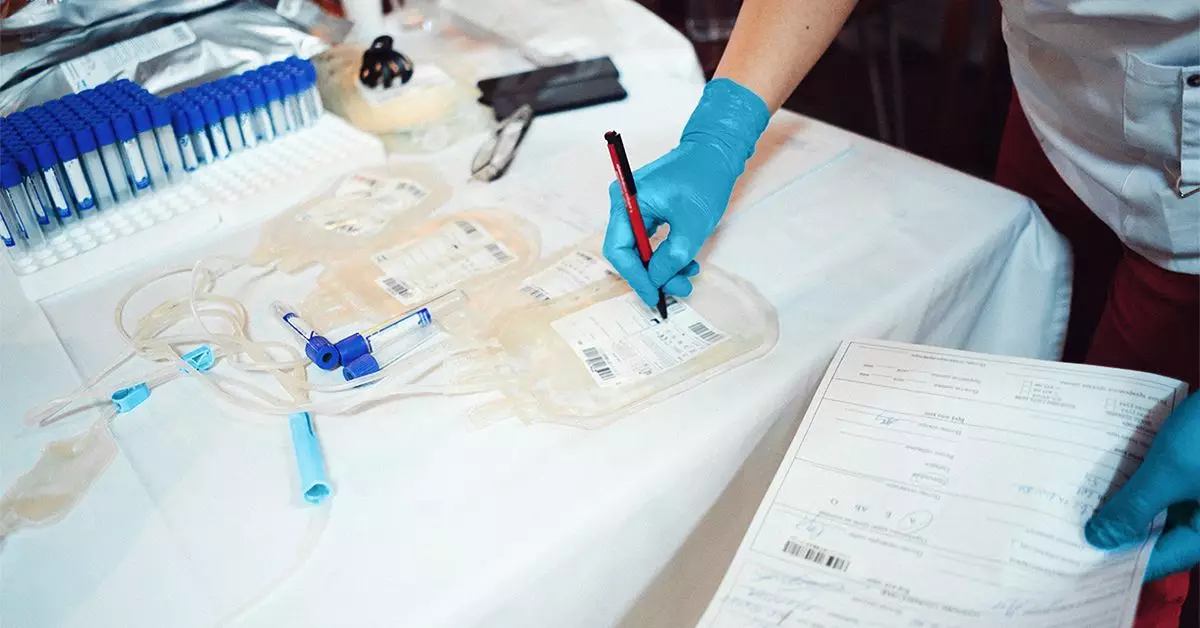

Before a blood donation takes place, every individual is subjected to a mini health assessment that scrutinizes critical health metrics such as blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and hemoglobin levels. This assessment doesn’t just act as a gatekeeper for the donation process; it often serves as a preliminary health check-up for potential donors. If abnormalities are identified—especially concerning hemoglobin levels—the donor may be warned against proceeding. This crucial step not only protects the safety of the blood supply but can also unwittingly signal that the donor may have underlying health issues, such as anemia or even leukemia.

Leukemia, while not routinely screened for, can manifest in the form of low red cell counts, which a mini health assessment might detect. An individual with such findings will be disqualified from donating, emphasizing how blood donation activities can lead to early detection and potential medical interventions.

Infectious Diseases and Their Connection to Blood Disorders

The protocol of screening donated blood for infectious diseases forms the backbone of ensuring donor safety and recipient health. Testing identifies a range of conditions, including blood types and diseases such as the sickle cell trait. A notable risk factor mentioned is infection with HTLV-1, a rare virus capable of triggering adult T-cell leukemia (ATL). This connection between infection and leukemia reinforces the need for comprehensive screening, particularly as patients suffering from these conditions often rely on blood transfusions.

If any abnormalities are found during testing—whether related to infectious diseases or not—donation centers typically discard the blood and may reach out to the donor for follow-up. This proactive engagement serves to safeguard not just the blood recipients but the donors themselves, fostering a culture of health awareness that extends beyond the confines of the donation process.

While blood donation is an act of altruism, it also unveils layers of complexity regarding health screening and disease detection. The procedures that protect the blood supply inherently support donor health awareness and early detection of potential life-threatening conditions like leukemia. Ultimately, the blood donation process stands not only as a generous gift to others but also as a crucial health assessment opportunity for the donors themselves. It encourages vigilance and necessitates an ongoing dialogue about how blood donation can serve dual purposes—saving lives and highlighting personal health imperatives.